Missile sites are Cold War

reminders: Most Nike bases turned into

parks

Carl Nolte, SF Chronicle Staff Writer

July 2, 2006

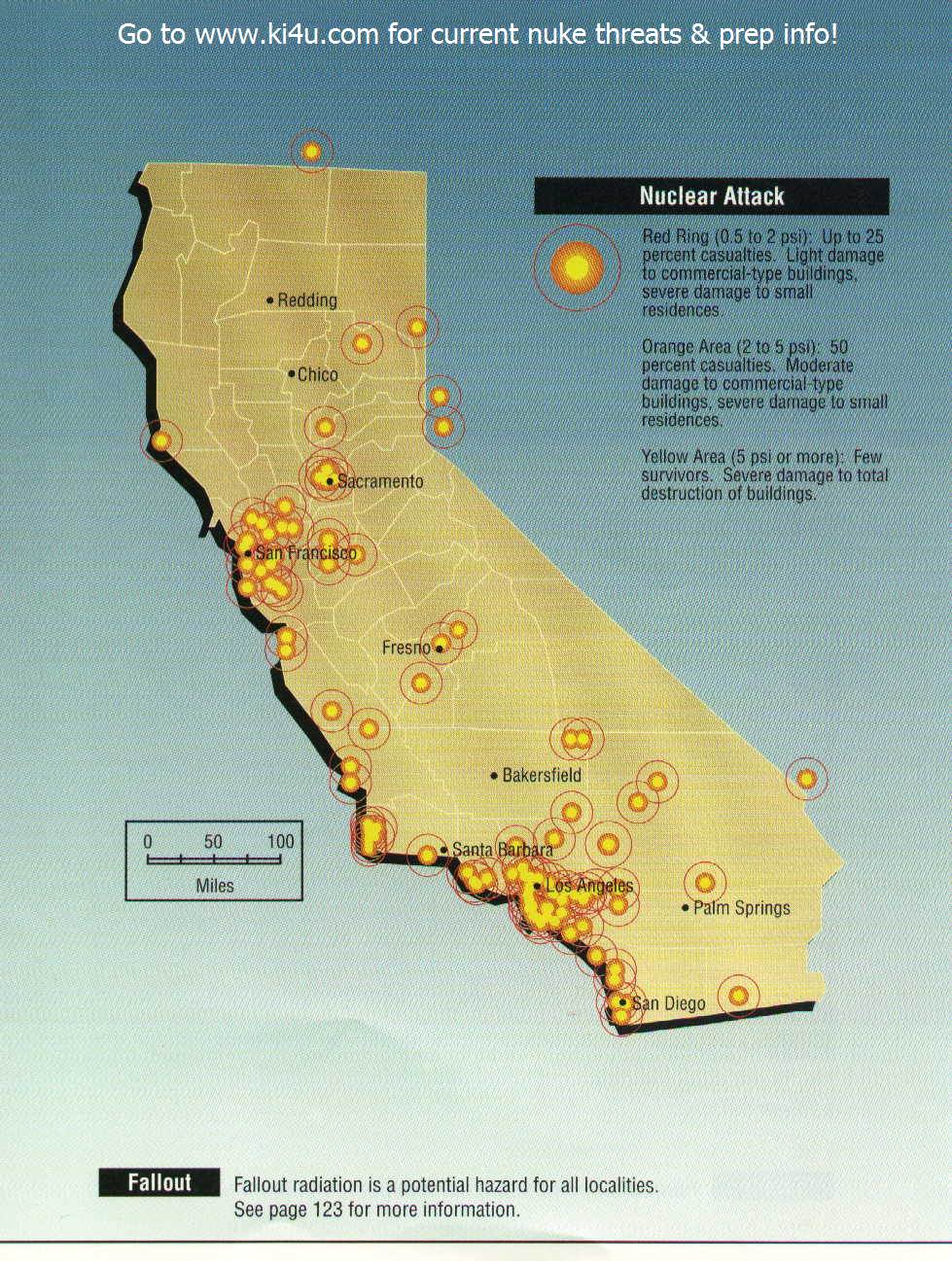

The news that North Korea may be close to perfecting a nuclear missile capable

of striking California brings back eerie reminders of another day, when the

United States lived under the threat of nuclear war. In those years, the enemy

was the Soviet Union and one of the prime targets was the Bay Area.

If the attack came, Maj. Gen.

Andrew Lolli once said, "most of this area would

unquestionably be destroyed.'' Lolli

Stopping the attack was his

responsibility.

Stopping the attack was his

responsibility.

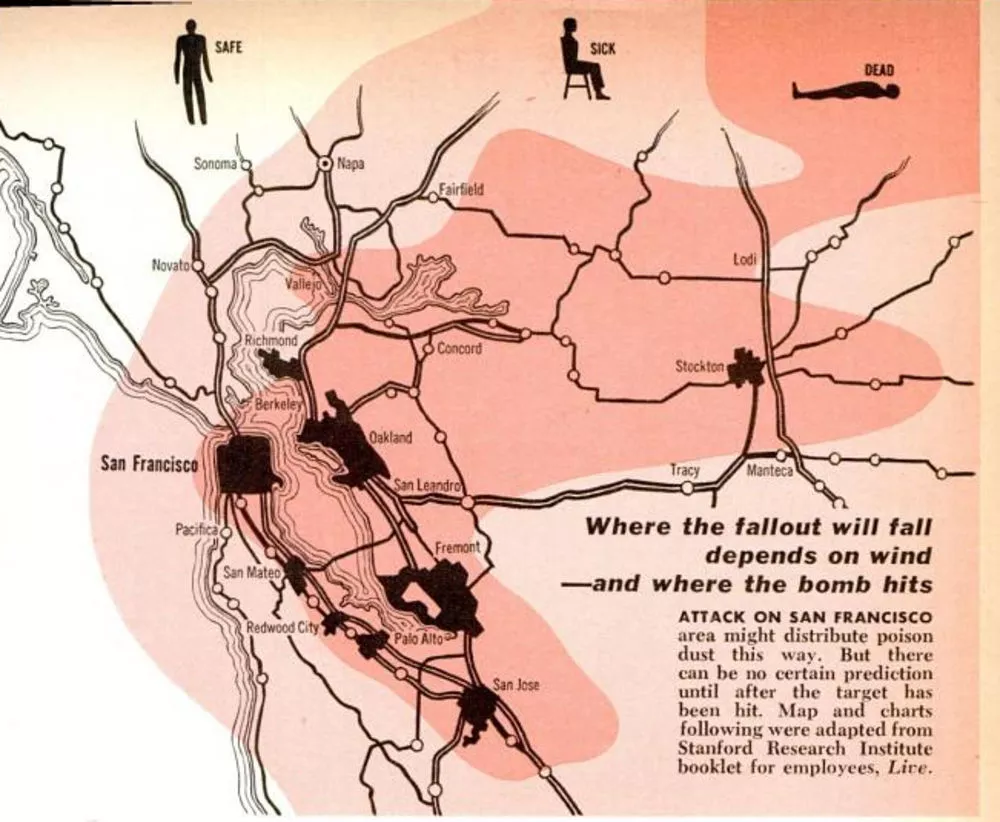

The Cold War seems like a thousand years ago now, but in those days the fear of

nuclear war was always in the background of life in America, and particularly

in the Bay Area. There were air

raid drills in schools and kids would practice diving under their desks. Not

much of a defense against nuclear weapons. Catholic schools added an element:

They prayed. There were signs all over most downtowns -- big buildings all had

fallout shelters.

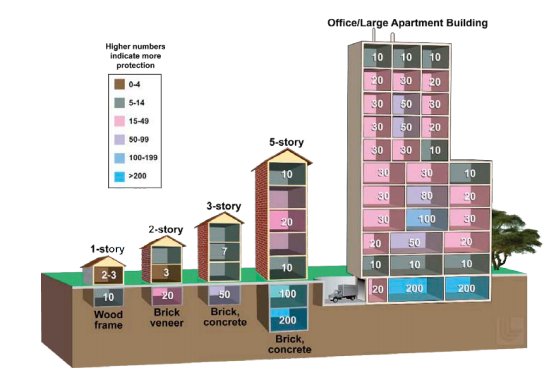

The government advised citizens that it might be a prudent idea to dig a family

shelter in the back yard and stock it with enough food to survive a nuclear

attack.

President John Kennedy called the

Cold War a "long, twilight struggle,'' and it was. Both sides had huge

stockpiles of weapons on the premise that if one side attacked, the other would

retaliate and neither would survive. It was a doctrine called mutually assured

destruction, or MAD, an acronym that was apt. The Soviets had us in

their sights.

The Bay Area was a target. There were a dozen military bases around the bay --

from the Pacific's nuclear submarine base at Mare Island, to the Alameda Naval

Air Station, to the Presidio of San Francisco, and more.

To defend the bases, there were

more than a dozen sites ringing the bay armed with Nike missiles designed to

shoot down Soviet bombers. These missiles first went into service in 1954 and

lasted until 1974. There were 300 similar sites around the country.

For 20 years, Army troops manned the sites, standing 24 hours on and 24 hours

off shifts, seven days a week. "There was no such thing as Christmas,''

said Lt. Susan Cheney, the last battery executive officer at Nike missile site

SF88 at Fort Baker on the Marin Headlands.

There were Nike sites at the Presidio and at Fort Funston near the zoo. There

was a site on top of Angel Island, sites on the Peninsula, in the East Bay,

including at Lake Chabot and in the Berkeley hills, and in Marin. What is now

the Marine Mammal Center near Sausalito was a Nike site.

sites on the Peninsula, in the East Bay,

including at Lake Chabot and in the Berkeley hills, and in Marin. What is now

the Marine Mammal Center near Sausalito was a Nike site.

The sites were controlled from the Mill Valley Air Force base atop the west

peak of Mount Tamalpais. This was the biggest

installation of the complex; it had radar to track incoming planes, barracks, a movie theater, even a bowling alley.

There were two generations of Nike missiles. The Ajax had a range of 25 miles

and could shoot down a plane traveling at twice the speed of sound. The later

Nike Hercules had a longer range -- 87 miles -- and could hit a faster plane.

It could also carry nuclear missiles.

The Army would never confirm or deny that the missiles were armed with nuclear

weapons. But there was little doubt.

" There were approximately 90 nuclear warheads ringing the bay, '' said

National Park Service Ranger John Porter, who has studied the Nike missile

system and is in charge of site SF88, which has been preserved in the Marin

Headlands. The Soviet bombers never came, and the missiles, like the giant

coastal defense artillery guns they replaced, were never fired. But there were

some close calls.

Stephen Haller and John Martini, two National Park Service historians, wrote a

history of the sites called "What We Have We Shall Defend." In it

they quote Terry Abel, an Army warrant officer who was stationed at the site.

He remembered "a little horrifying" alert during the Arab-Israeli war

of 1973.

The unit went to battle stations. "It was not a drill. It was not a drill,

it was not an exercise,'' Abel told Haller and Martini. "We had no idea at

the time whether the Soviets were launching a first strike, or what in God's

name was going on. ... Our little piece was getting those missiles loaded

properly and up in the air properly, as fast as we could. It was horrifying and

gratifying at the same time.''

Ron Parshall

remembered an earlier incident, a 15-minute alert, which meant the enemy would

be there in 15 minutes. "But we had that missile up in less than five

minutes,'' Parshall, who was an enlisted man, told

Haller and Martini, "so we had 10 minutes to spare ... and it's 'tick,

tick,' waiting for something to happen. We

thought we were at war. I definitely was very fearful at that time that we

would be at war, and then you start thinking that San Francisco would be gone

if we don't do our job.''

By the early '70s, it became

clear the Soviets would use intercontinental missiles, not planes, and the Nike

sites were obsolete. They were closed by 1974.

It was the end of an era in the

Bay Area in more ways than one. Haller, the park service historian, is fond of

pointing out that the Spaniards brought the first defense system to the Bay

Area in 1794 -- a brace of brass cannons that were mounted to protect the

entrance to the Bay.

The guns were cast in Peru in the 17th century and one of them was over 170

years old when it was mounted to protect the Spanish settlement in San

Francisco. "They may not have been on the cutting edge,'' Haller said

dryly.

So now Nike is a shoe and the

places where the missiles were have all become parkland.

Missile site SF88 has been restored to what it was when it was the last line of

defense of the United States. There are missiles in place, one of the first

computers, radar sets -- everything but warheads. It's located at Fort Barry,

in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. It is open to the public from

12:30 to 3:30 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday, and on the first Sunday of the

month, which is today. There is no charge.